We aim to remember: Affirmation and Belonging in the Lakota Oyate Homeschool Co-Op

Mary Bowman describes her homeland with grace: “We, the Lakota, live in Ȟe Sápa, The Black Hills. This is an ancient and very spiritual place for us….beautiful pine trees, rugged mountains, and prairie land. We hold very important ceremonies on this land.” She goes on to describe the beauty of the Badlands and the indignity of Mt. Rushmore, “that abomination” that sits at the spiritual home of her people.

There are about 100K remaining Lakota in the United States. COVID has hit Indigenous communities with ferocity. Indigenous families understandably worried that their children wouldn’t be safe returning to school in the fall. So they did something we associate with the most privileged communities – they started a learning pod.

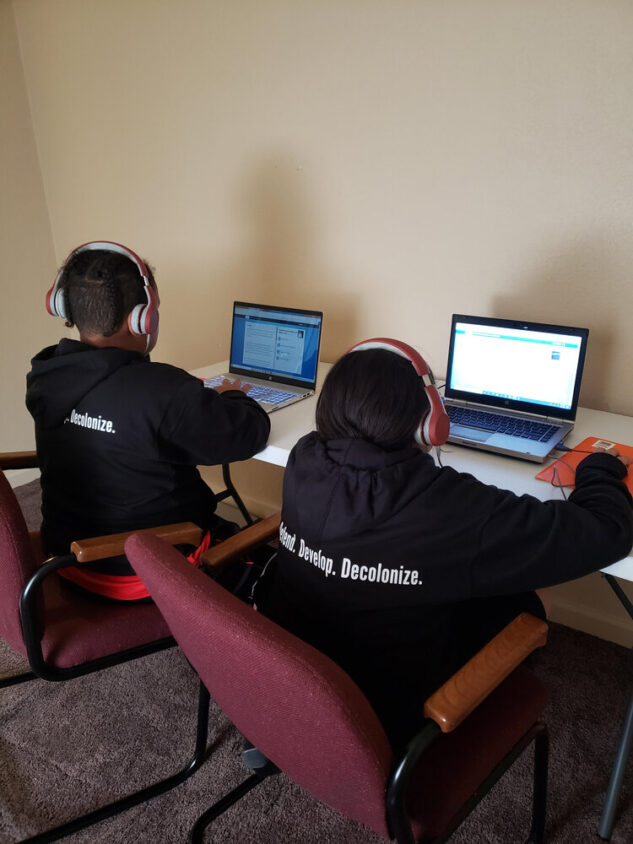

After posting a message on Facebook, Mary – a Lakota teacher – and a small group of parents, grandparents, and teachers received 140 messages from Indigenous families wishing to unenroll from their public district and re-enroll in the district on the neighboring reservation. During spring remote learning, high numbers of district students were disengaged – they just weren’t logging on. The district had no plans to reimagine the model for the fall. But the Oglala district would allow for pod-based remote learning embedded in the Lakota language and cultural curriculum.

It strikes me that these Lakota families were motivated by two realities: first, the lack of deliberate national or state action to make schools safe; and second, the importance of cultural – not just physical – safety for Lakota youth as a prerequisite for learning. Marie High Bear, now a pod teacher and mother to a young son, recalls, “My son didn’t feel as though he belonged [in his district school]…he was teased by the other kids for his long hair. I’ve had to explain to him that his baby hair is sacred to us.” For these reasons, Mary, Marie, and others in the community got together to design a learning model that would keep children physically safe and rectify centuries of inequity. “I’ve been an educator for 16 years working with indigenous kids in the public school,” Mary reflects. “I’d always say, ‘Work hard and you can change your life.’ I never got the buy-in, they just didn’t believe it. Plus, they would walk with their hands behind their backs all day, single-file. That’s just not how we treat our children.” Mary knew that this homeschooling pod could signal a longer-range shift for Native families by serving as a template for a more permanent Indigenous alternative education.

The Lakota Oyate Homeschool Co-op is grounded in the cultural knowledge and ways of being of the Lakota people. This shows up in everything from systems and procedures to core academics. The school day begins by smudging the school house, a ritual of burning sage and cedar, a practice that aims to “cleanse our minds, and make positive thoughts so that we can walk in a good way for our people, each other, and the Creator.” The pod has six children, ranging from 2nd-5th grades. They are taught together in this multi-aged group, which is supported by a whole community of family members. Marie serves as the “proctor” and Lakota Language and Culture teacher, working one-on-one when needed and leading the group during non-virtual learning portions of the day, such as nature exploration and hosting elders. Core academics like math and science are pursued in hands-on, practice-based ways. Students also spend time in nature during science learning, and math is grounded in culturally-relevant practical examples – a future lesson will be on how to erect tipis for maximum occupancy and egress. After the morning sage and cedar burning, the group then moves to a talking circle where the child with the feather or rock holds the floor. This is designed to be a reflective space for setting intentions grounded in Lakota values of respect, generosity, bravery, and courage. The children might reflect on the question, “What is a way that I can be generous today and share with others?”

As Marie describes the pod’s typical day, she keeps referring to the ways in which their learning community centers Lakota knowledge instead of relegating it to the boundaries of the day, as it had been in the traditional system. In March 2018, after decades of Native pressure, South Dakota adopted the Oceti Sakowin, a set of essential understandings and standards aimed at addressing cultural diversity and raising consciousness to empower Native American students. Marie shares that the implementation of these standards was relegated to “specials,” once a week language classes, guest speakers, or other random experiences. This knowledge wasn’t embedded within the core DNA of school (e.g. daily rituals, curriculum) in ways that were relevant to Native and non-Native learners alike. This learning pod presents the opportunity to do what decades of advocacy couldn’t – center traditional knowledge on Lakota terms. As Mary Bowman says of the assimilative nature of American education so far, “The boarding schools tried to make us forget, but we aim to remember.”

I was also delighted by the presence of nature – dwelling in and learning from it – within this pod. Young people spend time outside studying plants and flora. They learn about the healing powers of natural remedies and the fundamental balance of all living things. They learn about geology and Lakota Star Knowledge, an ancestral tradition used for sacred events such as solstices and to observe the seasons in their sacred order. They eat lunch in a circle outdoors. They tell stories about the buffalo during story time, as Marie encourages them to illustrate what they hear. There is a wholeness to this learning environment that engages young people cognitively, sensorily, spiritually, and physically. In the age of COVID, with millions of children staring at screens, this is a rarity. For the Lakota, this vital aspect of their cultural and spiritual lives is left at the door in mainstream schooling.

I was introduced to The Lakota Oyate Homeschool Co-op because they are recent recipients of an Enduring Ideas Award, a fund of Teach for America’s Reinvention Lab that I Co-Chair with Sunanna Chand. This co-op is such an intriguing example of reinventing because it adds a much-needed dimension to our discussion on learning pods, equity, and the path for public education in a post-COVID world. While it is too early to render a verdict on pods, the most popular narrative frames them as tools of privilege – yet another way for more affluent (and mostly White) families to hoard resources and opportunities for their kids. In some cases, that narrative is fair and true; in others, it’s incomplete. In this instance, the learning pod is almost an historical corrective.

In this Lakota community, the road to “reinventing” is about reconnecting to knowledge and ways of being that have been long marginalized and undervalued by the traditional system. Mary Bowman, who is also a fellow with NACA Inspired Schools Network, which works to build Indigenous community schools, believes this pod is the way of the future. While her dream of establishing a Lakota community school predates COVID, she sees this as an unprecedented opportunity to prove what is possible in creating equitable, culturally affirming learning environments. I see this community making tremendous leaps towards Affirmation of Self & Others, Connection & Community, Relevance, and Whole-Child Focus through their deep commitment to culturally-responsive pedagogy. These leaps – while important in their own right – also enable better academic learning. Both Marie and Mary describe how a learning environment that fosters deep connection, sense of self, and pride creates the conditions for better academic progress and far fewer behavioral challenges. For Co-op students, a deep sense of belonging is the foundation for academic engagement and true learning. This community’s learnings could very well influence the public school district and create the demand for more Lakota-run community schools, grounded in Indigenous knowledge and facilitated by Indigenous teachers.

When I stepped away from our conversation, the school day that Marie High Bear described somehow felt familiar to me, even though I’d never been to this classroom-in-the-living-room. I realize that many of the innovations communities are seeking – particularly the “whole child ones” – try to capture the sense of wholeness, mindfulness, and respect for other ways of knowing and being that are at the center of Lakota life. As we move forward in reinventing learning, we must continue to ask ourselves: what counts as valid evidence and knowledge, and from whom does it count?

WHAT THE LAKOTA OYATE HOMESCHOOL CO-OP IS TEACHING US ABOUT ROADS TO REINVENTING:

- The science of learning and development confirms that having a sense of belonging and eliminating identity threats is a prerequisite for learning; the Co-op brings this lesson to life by creating a safe environment, grounded in Lakota language, and culture where learners can thrive.

- Innovation isn’t always about inventing something new: this powerful example of applying Indigenous knowledge in new contexts suggests a road grounded in reconnection and remembering.

- Learning pods can support the traditional model of school and districts to evolve.

- Many “modern” school design innovations highlight practices that have long been part of Indigenous cultures; we must be mindful of which kinds and sources of evidence and knowledge are deemed valid.

Transcend supports communities to create and spread extraordinary, equitable learning environments.