Innovation is Only as Strong as the Space Created for It

After attending private, public, and a short homeschool experience, and teaching and/or visiting schools in Los Angeles, Denver, Botswana, Japan, Papua New Guinea, and Boston, Elisha envisioned and became the principal of Denver-based STRIVE Prep-RISE, a social justice, college prep high school serving all kids. The backstory of our school is important to understanding how the vision for RISE was born. It wasn’t something that happened in year zero; it was decades in the making, and continues to evolve even as this piece is being written. RISE is an open-enrollment, Title I public charter with 87% FRL students and 97% students of color. Of course Elisha didn’t do this innovation work alone, and it was only with the help and dedication of incredible teachers and the support of our STRIVE Central office that this work was born and raised in the outskirts of Denver in a community that has long suffered under the types of neglect that befall public schools in low-income neighborhoods. Our innovations now give us as much stress as any other wonderful project purpose-built to help teenagers, but the journey, process, and the results have been worth it. Allow us to explain how we got to where we are.

In 2017, RISE applied to be a part of the Transcend + NewSchool Collaborative designed to help educators reimagine the core structures of school. With Transcend’s guidance, we learned the principles of design thinking and prototyping. Most importantly, we were given space and inspiration to think more deeply about why and how RISE scholars experience learning and the methods by which we teach them. During our first convening for Transcend, a few key ideas would become the blueprint for the signature experiences we now offer at RISE. With repeated convenings with Transcend in San Francisco, Austin, and Brooklyn, we brainstormed our signature experiences. We had no idea that we would be changing the future of RISE and the formal experience of schooling for our scholars. Setting aside time and space for reimagining school gave us the “go-ahead” to innovate and to not be scared to fail, iterate, or change everything we were once used to.

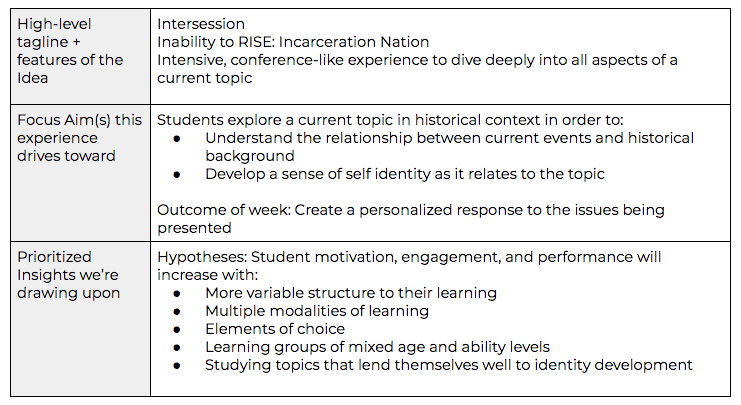

During the first convening in October of 2017, while other groups were planning what they were going to prototype for the following year, we were busy thinking through how we were going to launch our first innovation even sooner—in January. It was going to be called Intersession, and the focus of study would be mass incarceration. We only had a few months to identify the ways in which traditional schooling and curricula sometimes can feel for our scholars—restrictive, neglectful, biased, boring, and futile—and to redesign a new, relevant, and culturally responsive educational experience that would not only empower our scholars, their families, and their community but also would encourage and inspire them to do better and remain curious and engaged during the rest of the school year.

We took on this massive goal to begin the innovation right then and there because we couldn’t ignore the school bus-sized elephant in the room: That innovation is desired but not required. School systems face a plethora of roadblocks, including and especially the deprioritization of innovative ideas, which often are pushed aside for other “pressing” concerns. Similarly, it’s easy to conclude, “Let’s wait ‘til next year when conditions are better.” But a tag line from our Brooklyn convening about structural reorganization rang in my ear: Your organization is perfectly designed for the results you are getting. We could not shake that sentiment; if we wanted our kids to care about social injustices, then we would have to teach about them through myriad angles so our scholars’ comprehension was both swift and meaningful.

Even though there are countless issues that face public schools—especially Title I charters in underserved areas—we pressed on. The challenges—and potential distractors—we faced included everything from addressing transportation and safety issues to shared space issues between two schools on one campus to begging to have an entire weight room not be on our only stage. These challenges threatened to stultify innovation. Despite these barriers, we were able to design for our scholars an authentic, collaborative experience. Here’s how it took shape.

To launch Intersession, we showed the documentary 13th to the entire school. We introduced the film with a rhetorical analysis presentation from sophomores who that previous semester completed our first ever concurrent enrollment English composition course, and we used Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow as our anchor text and Intersession framework for both staff and scholars. What followed were multiple different modalities of learning.

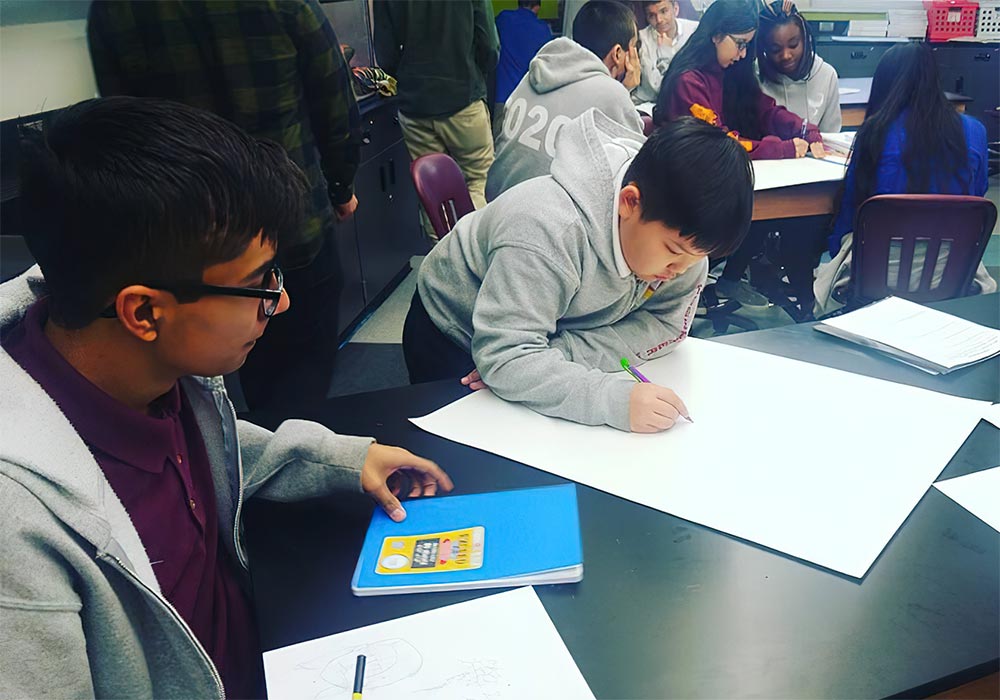

Our team designed sessions that included an ACLU “Know Your Rights” training for scholars so they could walk away with how to interact with the police, what their rights are in those moments, and how to stay safe. Small business owners showed scholars how to create their own hats, buttons, and shirts in order to wear their activism. In small groups, peers shared their stories about their relationship to and experiences with unbalanced systems of justice. Authentic and organic moments of intimacy and vulnerability erupted during final presentations where the entire school listened to one another for three hours. For us, it was paramount to bring a learning experience—and topic of extreme relevance—where learners were the center of attention and where their stories and voices were a part of constructing the curriculum.

The innovation did not come without some push back. As a result of talking about what some see as a controversial topic (such as Black people’s tenuous relationship with police officers), some white parents reported their scholars were uncomfortable at school for the first time. This was outside their comfort zone. In reflection, this might have been the first time where top-to-bottom white history, experiences, and perspectives were not the dominant narrative or the topic sentence of the lesson. Their reaction reminds us of the “shock to the system” that Robin DiAngelo describes in White Fragility (our network-wide book study this year) and that happens when such issues are addressed in white communities for the first time. But this invaluable conference-style week became a bridge to innovation. Although it ruffled feathers and challenged our teachers and their skills, ultimately it brought our school closer together. The uniqueness of the experience and our scholars’ response was—and still remains—a source of pride for our young school.

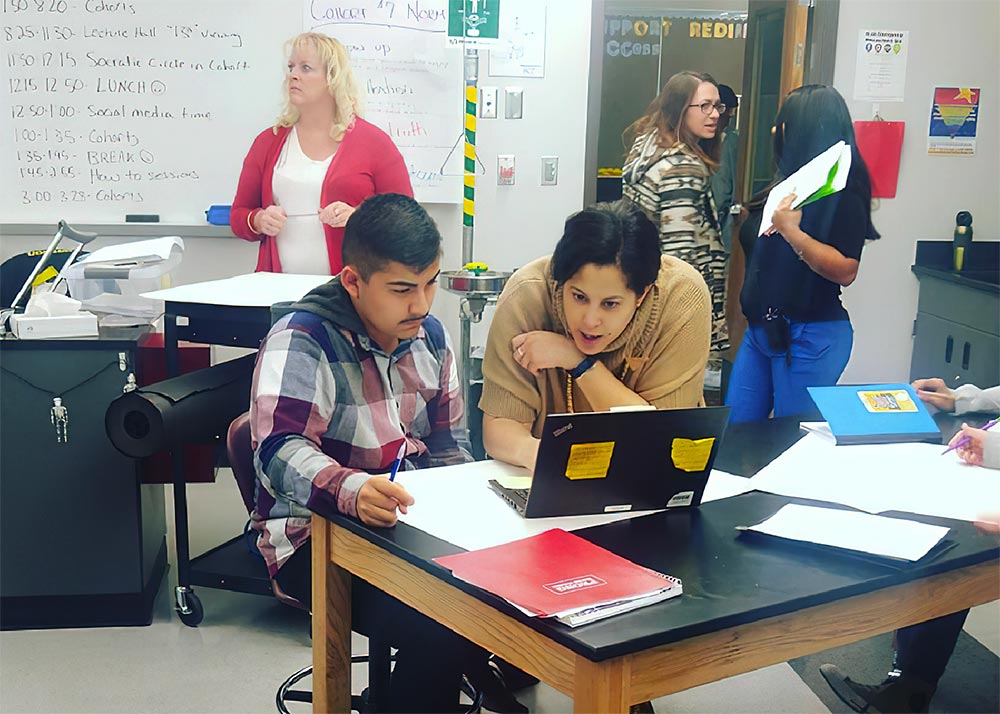

To deepen the Intersession signature experience, we built a new school day structure and developed a common vocabulary that would connect us all. Intersession became a week when the typical teacher-student power structure was challenged. All grades (at that time just freshmen and sophomores) were all mixed together and divided into cohorts led by one or two teachers and staff, who were also mixed by content and grade levels. Staff and scholars read excerpts of The New Jim Crow and held discussions on race and microaggressions in American workplaces and schools. The week included discussions and presentations in cohorts around mass incarceration and breakout choice sessions about topics such as juvenile crime stats and how racism makes black people physically diseased, as Douglas Jacobs explains in “We’re Sick of Racism, Literally” from The New York Times. Many teachers facilitating these racial injustice discussions (of their own design and some assigned) were new to the material, concepts, and realities laid out in The New Jim Crow. But this new format sought to teach each scholar a new skill that they wouldn’t have a chance to learn in a typical school setting.

We found that transitioning our regular school day schedule away from classes divided by periods and towards scholars selecting topics of interest and collaborating with different teachers and peers daily was purely to their benefit. The change increased our scholars’ exposure to real world, applicable knowledge, empathy work, and hands-on learning. Here is an outline of our first prototype of Intersession:.

Again, all we did to build this signature experience was provide the space, time, and resources to create optimum conditions for deep, active learning. Now that our first Intersession, which was called: Inability to RISE: Incarceration Nation, is under our belt, we are building more and improving the experience. Each year at RISE, the staff selects an area of social justice that we focus on for the year, weaving the themes of the topic in all content areas throughout the year. Our longer term idea is to make Intersession more connected to everyday curriculum in order for scholars to see a direct connection between what and how they learn over time as well as the impact it has on their identity and development.

Here is one scholar’s take on the effectiveness of Intersession:

“America is currently a harsh contrast to a typical RISE classroom. But because of a RISE classroom, future leaders, doctors, poets, mathematicians, and activists will go into the future America to make it great for possibly the first time ever. One week will not change the perspectives of every person forever. But that introduction to change can at the very least get someone to start wondering, then thinking, and eventually challenging. And it is only when the powerless begin to challenge, that they become the powerful…When someone asks why they have to learn math, unsettling statistics about wealth and education in relation to race are brought up.“

-Haley, RISE scholar

So many times schools aren’t given what’s required to innovate. But we cannot wait for the time and space to be given to us. We must make the time and space because our children cannot wait. Their futures are too important. The good news is, as we’ve now experienced, once the spark of rethinking is lit it cannot be contained.

Anna Steed was born and raised in Denver, CO. She attended some of the best public schools in Denver, which included a Montessori elementary school, a performance arts middle school, and a nationally-ranked high school. Anna left home to pursue her Bachelor’s degree at Wesleyan University, graduating with a double major in English and African American Studies. Being a part of the Institute for the Recruitment of Teachers led Anna to graduate work at the University of Maryland where she earned her Master’s degree and completed PhD coursework and exams in English Language and Literature. In 2014, Anna returned home to Denver to be closer to her family and to continue teaching. She is a 13-year veteran college English instructor, and in her 4th year of teaching at the high school level, and she absolutely loves it. During its founding year, Anna taught 9th grade ELA at STRIVE Prep–RISE, a Title I public charter in Denver. She created the RISE Speech & Debate class and built her team that is now nationally-ranked. Anna also teaches English Composition at the Community College of Aurora and as a concurrent enrollment course at RISE. With a life lived in the classroom as both student and teacher, Anna is reminded everyday about how lives are impacted where education is involved, or most woefully, when culturally responsive and responsible education is not involved.

Elisha Roberts is a Principal at STRIVE Prep – RISE, and Managing Director at STRIVE Prep – Montbello. She has a bachelor’s degree from Occidental College and a Masters of Education, Curriculum and Instruction from Boston College. She has six years of classroom teaching experience and was an Assistant Principal at STRIVE Prep – Excel for one year, overseeing the Student Intervention team and creating and implementing culture systems. In 2016, she founded STRIVE Prep – RISE, a new high school model for the network built on a social justice focus, a restorative culture system, and an unapologetically college-going culture. RISE has been one of the highest rated high schools in its region, and now in her fourth year as RISE’s Principal, Elisha is expanding her scope to support additional STRIVE Prep schools. Elisha was born and raised in Denver, and spent time living and learning abroad in Botswana, Papua New Guinea, Japan, and other parts of S.E. Asian and Europe. She has a fiancé and a daughter whom she treasures.

For the past three years, Samson Patton has taught 10th grade English Language Arts at STRIVE Prep – RISE High School, having previously taught 6th and 7th grade ELA in San Antonio, TX. He is currently pursuing his masters in Secondary English Education at the University of Colorado – Denver and has focused on community responsive teaching. Specifically, implementing discussion based classrooms that seek to put the scholar at the center of problem-solving and text-comprehension so that scholars can read the word and the world as they learn how to navigate within it.

Transcend supports communities to create and spread extraordinary, equitable learning environments.