How Project-Based Learning Is Transforming a Rural Community

Clear Creek School District (CCSD), nestled amidst Colorado’s majestic peaks, serves about 700 students from Clear Creek—a rural county of nearly 10,000 people and 400 square miles that stretches from the start of the Rockies just west of Denver to the 10th-highest summit at Grays Peak.

But the idyllic mountain setting obscures a fact about the school that can’t be ignored: The water is undrinkable.

“We haven’t been able to drink our school’s water for the last several years,” says Melissa English, a biology teacher at the school. The local water utility notifies the district about the presence of high levels of two chemicals that are part of the treatment process, especially during high run-off times in the spring and summer. These chemicals have raised concerns around the question of deteriorating into carcinogenic compounds.

So the custodial staff distributes water jugs to dispensing stations located throughout the middle and high school, passing by the school’s cafeteria, the principal’s office, and classrooms on their way.

Those classrooms are where recently graduated senior Reese used to sit in her freshman classes, not feeling challenged and not feeling inspired. “My freshman year was disappointing,” she said. “I took classes that didn’t push me.”

From his seat as the principal, Chris Gould saw the disengagement in students at the school.

If we can’t engage our students, then they won’t learn anything.

Principal Chris Gould

The scene at Clear Creek High School is not unlike scenes playing out at schools across the country—students sit disengaged in classrooms as lessons focus on irrelevant rote facts when real-world issues, like the lack of drinking water, are begging for creative solutions.

But not in Clear Creek. Not anymore.

The Challenges Facing Clear Creek

Once the home of the world’s largest gold mine, Clear Creek County has found new life as a tourist destination. Nearly 60% of Clear Creek’s jobs are related to tourism, but most of the jobs are low-wage and dependent on seasonal variations. The influx of wealthier people seeking mountain escapes has raised home values and taxes, and long-time residents have had a hard time keeping up.

The county’s population growth has flatlined, and—like many districts in Colorado—CCSD has seen decreasing enrollment. Enrollment overall is down over 50% in the last 10 years. During the 2020-2021 school year, there were 232 students enrolled in Clear Creek High School; that dropped to just 189 for the 2023-2024 school year. Per-pupil-funding equations exacerbate the issues caused by declining enrollment because fewer students means less money.

This hasn’t discouraged CCSD; instead, it’s deepened the district’s commitment to designing experiences and supports in schools that meet students’ holistic needs academically, mentally, socially, and emotionally. “In the wake of the pandemic, when we were in the midst of that mental health crisis, it was clear that we needed to find ways to help students engage,” says Gould.

A Call to Rethink Education in Clear Creek

When former superintendent Karen Quanbeck started at CCSD in summer 2019, she embarked on a listening tour across the district aiming to truly understand the concerns of educators, families, and students.

“Kids reported that there was high teacher turnover that was super frustrating. I remember them begging me to find a science teacher who would stay,” says Quanbeck. “The biggest, most concerning, thing that I heard was that kids who didn’t necessarily know how to do school, kids who you might consider to be from higher-poverty situations, or from tough home situations, were the least engaged.”

Education leaders in the community began to wrestle with some big questions: How can schools adapt to prepare our students for a changing economy? How can schools cultivate homegrown talent for a thriving community? How are our schools part of the economy?

Being a small, rural school system can often mean there are major capacity constraints that make daily operations a challenge and forward-thinking innovations feel like an unreachable dream. But this challenge is arguably Clear Creek’s greatest asset: The tight-knit relationships at the heart of rural areas help entire communities mobilize.

Superintendent Quanbeck brought together a wide range of community stakeholders around a common call to action: to rethink how school is preparing Clear Creek’s young people to thrive, contribute to, and transform their community.

We couldn’t do it alone.

Former Superintendent Karen Quanbeck

Parents, students, business leaders, and politicians all answered the call. In rural communities, school plays an outsize role in community life and social services, and community members believe change in their community starts with change in their schools.

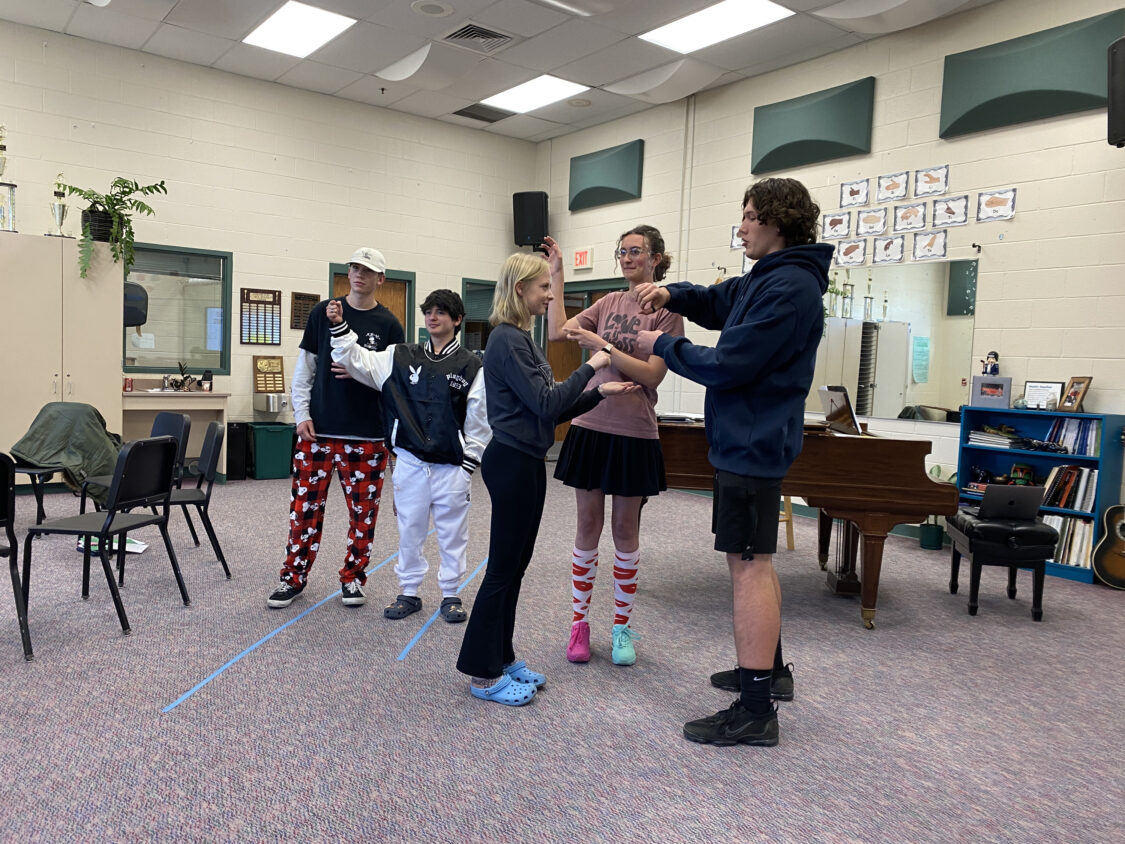

With support from Transcend, Clear Creek’s design team—a group of students, teachers, staff, and leaders who are driving the redesign work—decided what innovation they wanted to prioritize first. While teachers and staff advocated for moving towards portfolio-based assessments, young people had a different idea.

Principal Gould recalls a meeting where one shy eighth grader on the design team sternly said: “Projects are important for me to learn, and I need to see them in math and social studies.”

And when students say what they want and need from school, it’s hard to deny them.

Leveraging Place In Learning

At the beginning of the 2023-2024 school year, Melissa English’s biology students—including Reese—were learning biochemistry, the study of the basic building blocks of life, like water.

The students started asking questions about how what they were learning relates to the water in the school. Then they asked: “Could we try to delve more into what is wrong with the water in our schools so that we can maybe help to formulate a plan for how to fix this?”

So the entire curriculum—one of 34 classes incorporating some project-based learning—is focused on the water crisis in Clear Creek. Students in these career-connected learning classes are breaking out of the four walls of their classroom to explore legitimate challenges their community faces, all while learning and applying content.

In biology, that means learning all about filtration systems, water quality, and the industry of distributing and cleaning water. The students broke into smaller teams based on their unique interests. Reese led communications to fundraise, engage with industry leaders in water distribution, and liaise with school and district leadership; another student attracted to scientific experiments ran comparisons between filtered water, bottled water, and natural water; a student interested in art made posters to raise awareness; and yet another student became an investigator, digging into all kinds of codes and records. “He’s realized his true passion is criminology because through this process, he went through all of the legal actions,” Reese says.

People are learning who they are through this project, which I think project-based learning helps [students] do.

Reese, Clear Creek student

The students tested solutions like purchasing a carbon filtration system for faucets throughout the school and presented their learnings and recommendations to the school board. In next year’s AP Environmental Studies class, students will carry out a year of water testing to get data that will give a more complete picture of seasonal fluctuations. They will also test at three different points in the water system, including the point of entry from the water utility into the school system and at the point of use in the building.

In another pilot class, students are learning how to build mountain bikes, maintain the bikes, and even build trails for them. “Even if they aren’t interested in a career that is exactly using what Bike Tech taught them, they are able to gain skills they can translate to some other business in the area,” says Principal Gould. “We have students who will probably not travel far from home once they graduate from Clear Creek, and we are hoping that as we develop more of this project-based learning, they will have even more skills they can offer up as they look for jobs in the community.”

Sustaining Progress and Innovation

During the 2022-2023 school year, Superintendent Karen Quanbeck and the elementary school principal both moved onto roles outside of the school district. Like many school systems all across the country, when a visionary leader leaves, they risk taking the vision with them.

But the conviction runs deep in Clear Creek, and district leaders and community members remain fiercely committed. Both the incoming superintendent, Dr. Thomas Meyer, and the incoming principal, Brandi Wheeler, plan to continue the innovation. “During my short time in the district, I have heard amazing things that are happening, along with all of the energetic and bold plans for the future to benefit our students, their learning, and their futures,” Meyer says.

And the projects in classrooms are making a difference. The board has committed a minimum of $150,000 to mitigate the water issues. “Now that people are seeing what it can do, I think it’s making a lot of people get behind the idea of bringing change to the school,” Reese says.

For Reese and her peers, the change has been about more than seeing increased student engagement and reduced absenteeism; it’s fundamentally changed how she thinks about herself and her place in the world.

I used to think I didn’t have a purpose, but now I know I do. There are so many things in this world that are meant for me to do.

Reese, Clear Creek student

Transcend supports communities to create and spread extraordinary, equitable learning environments.